When to Delete Files

By now we’ve studied a variety of organizational questions relating to filesystems in detail. But here’s a seemingly foundational one we haven’t touched yet: should we be keeping many of our files at all?

On the one hand, it seems as if we shouldn’t have to worry about keeping them: files in the digital world take up no physical space, don’t have to be laboriously dragged around when you move or shoved in storage lockers, and really can stay “out of sight, out of mind” in a way that physical objects can’t. On the other hand, certain kinds of files could be large enough to require you to buy another hard drive or slow down your computer, and regardless, having too many files to think about can still overload your brain even if it doesn’t overload your computer.

As with so much else in life, the answer should be about finding an appropriate balance.

Why delete junk?

Many people don’t count digital clutter as clutter. I used to be this way myself; I figured storage space was cheap, so what was the point of deleting anything? The problem is that junk is still junk, no matter how little money it may cost to keep it. Files that you never use or look at clutter up your computer and your hierarchy and make it harder to find the things you do want. And just like clutter in your house, when it builds up slowly, you might not realize how messy things are until you finally clean it out.

Some files do have sentimental value. I’m young enough to have some computer files I made all the way back to when I was 5 years old (at least some of them are still readable on a modern computer), and browsing through projects from past ages can be a fun way to spend a Saturday afternoon once in a while. And I’m certainly not suggesting you delete old projects that might be useful as references later. But most of us periodically produce or download files that we can tell will never be useful again (or that never were useful!). Those files are the digital equivalent of trash. Do you keep all your trash in your house?

One useful compromise for items that fall somewhere in between

is to place them into an old folder

for that project or domain

– much like putting physical items in your attic or a storage locker.

That way, they stay out of your way

unless you explicitly go looking for the junk.

Even here though, it is important not to indiscriminately dump things

into the folder.

The folder should still be organized

(for instance, I have a folder of software I’ve written

but don’t expect to use again,

organized neatly into stuff I started working on and abandoned,

stuff I used for some time but is no longer useful

– for instance, it integrated with software at my college –

and stuff I wrote as an exercise for educational purposes).

And before you dump things into the old folder,

ask whether there is actually some reason

you might conceivably need or want to see it in the future,

or whether it’s just trash.

Tip:

Ideally, the old folder shouldn’t be inside the main folder

due to the Single-Question Principle.

Instead, you can add an additional hierarchy level:

in my Software folder, for instance,

the first level contains only two folders,

Active and Inactive,

with Inactive corresponding to the old folder.

This may not be worth clicking through an extra layer of folders

if you only have a couple of old items,

but if you get to the point where you have a substantial archive

of inactive items that you don’t want to delete yet

and you access frequently, it’s worth considering.

There is one more reason to delete some kinds of junk: anytime you have data, it’s vulnerable to security and privacy breaches. Even seemingly harmless data can tell more about you than you’d think when someone gathers enough of it together. And if you don’t have the data, nobody can steal it. As an average person not in charge of a business, it’s probably not worth developing paranoid retention policies and deleting even data that could still be useful in order to mitigate this risk, but if data isn’t providing you any obvious benefit anymore, this may be a great excuse to axe it.

The Spectrum of Value

In attempting to answer questions of moderation and balance, we can get a great deal out of creating a scale or line of some kind. At one extreme are files that cannot be recreated at all and you will definitely need again. Imagine you’ve been subpoenaed for some business records but haven’t delivered them to the court yet. You certainly want to save these files. At the other are files that you downloaded off the Internet and you know you will never want to see again. Imagine you accidentally downloaded malware or some disgusting hate speech. You certainly want to delete these files.

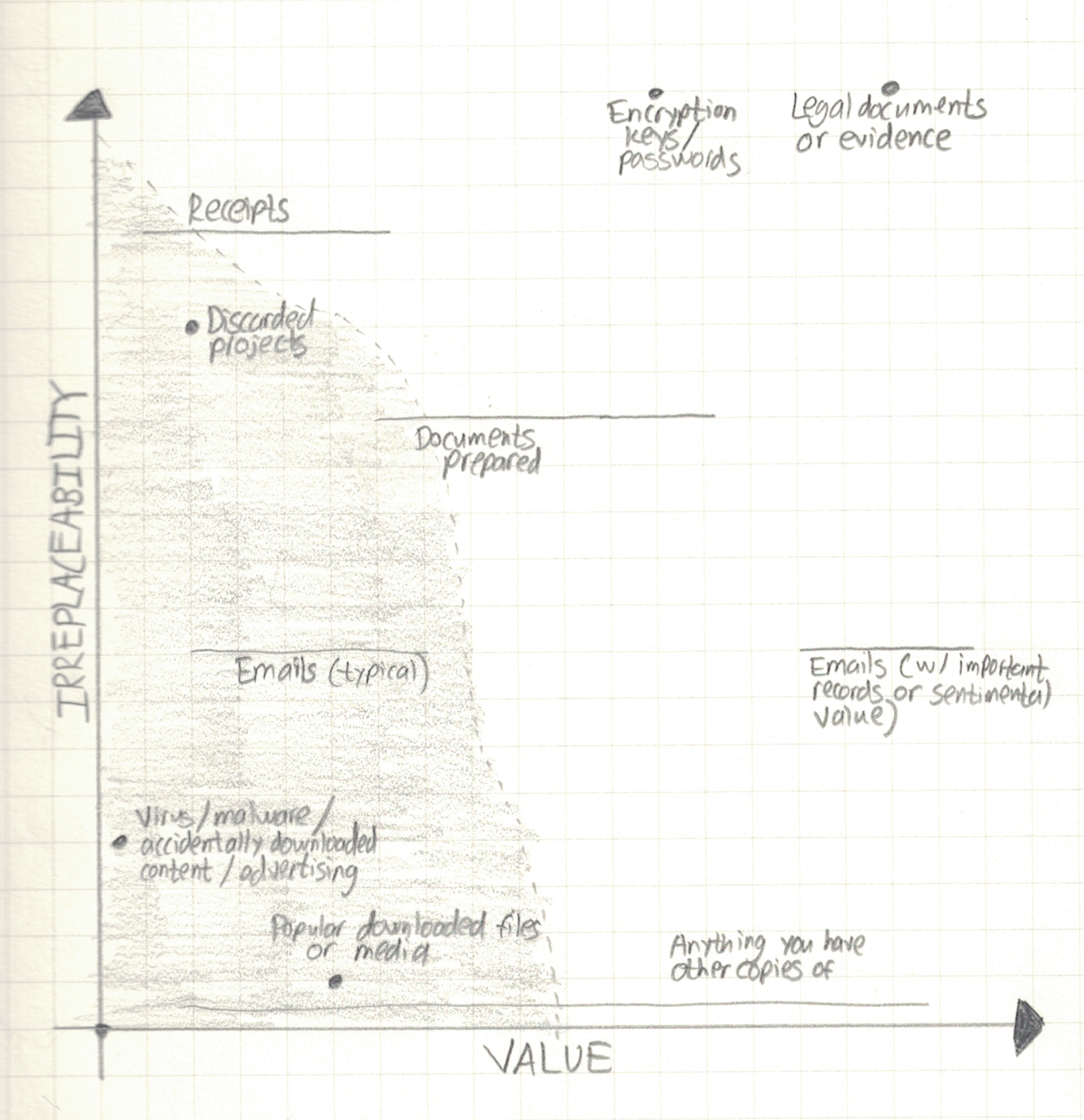

That I mentioned the same two factors for both suggests we actually need two axes to properly represent the situation: one for replaceability and one for usefulness. Here’s a sample version of this model; the shaded region represents files that make sense to delete.

Of course, depending on your data, values, and individual needs, you may place certain things in different places on the graph than I have or draw the dotted curve in a different way than I did (I kind of just made it up). The point is that value and irreplaceability work together to determine whether it’s worth keeping files. Only files that have value to you should be kept, but the more irreplaceable something is, the lower the threshold of value needs to be before keeping the file is justified.

Note: Despite many emails falling into my shaded region above, I actually don’t delete emails on a regular basis. Most of them are completely useless, but I get so many emails that I find it more efficient to hit “archive” on everything and wade through piles of useless emails when I have to find something than to neatly sort every email when I get it. Once every few years, though, I do go through and scan for types of emails that take up disproportionate amounts of my inbox (e.g., marketing emails from a particular company, periodic notifications from one website). I then do a search that brings back all of those emails and highlight and delete all of them. This can cut out a remarkable amount of the junk in only an hour or two, so it makes a good compromise.

Specific Tips

- Unless you’re dealing with commercial-scale amounts of data, never delete anything that is both valuable and irreplaceable. Storage space is so cheap nowadays that this never makes sense.

- If something is valuable but entirely replaceable, just trash it. For instance, with today’s Internet speeds, it’s rarely worth keeping software that you can redownload should you need to install it again. (But if it’s uncommon enough that there’s a real risk you won’t be able to download it a couple years down the line, keep it.)

-

If you need to save hard drive space, go after:

- Useless files (temporary files that programs didn’t clean up, files in your Recycle Bin or Trash, and so on).

- Software you no longer need.

- Videos.

- High-quality pictures and audio.

- Downloaded data dumps or other scientific/technical resources.

Very few other files ever take up enough space to be worth spending your time picking through. When you delete those files, it should be to get rid of clutter and not to save space.

-

Wondering when you need to save hard drive space? A good rule of thumb is that you shouldn’t let your hard drive get more than 80% full. More can start to slow down your machine, particularly if you have a solid-state drive. Not sure how to check how full your drive is? In Windows, open Computer (fastest way: press Windows+E). On a Mac, open About This Mac from the Apple menu and choose the Storage tab. On Linux, run

df -h.Windows and Mac have built-in tools to help you identify items you may be able to delete, as well; on Windows, search for

Storagein the start menu, and on a Mac, click the Manage button in the About this Mac window mentioned above. - Remember that you can always retrieve something you deleted from a backup if you delete something and shortly afterwards realize you actually needed it. (You do have a backup, right?) This may make you more comfortable about deleting things; it certainly makes me more comfortable.