How to Slow Down

Reading and thinking lately, it’s becoming more and more clear to me that we all feel the world is moving too fast. I don’t pretend this feeling is unique to the present day; people have been grumbling about change throughout recorded history (and most likely long before that), and change is ultimately the cause of our perception of pace. I am claiming that the actual pace at which information is delivered is unprecedented. Now, when President Trump tweets something, hundreds of thousands – maybe millions – of people across the entire world will read it within a few minutes. (Trump has almost 66 million followers as of today.)

It’s all well and good to talk about how amazing this technology is, and we do plenty of that; I don’t need to do any more of it myself. Ultimately discussions of how cool or remarkable the Internet is are frivolous. The results of this kind of speed on our society and on us as individuals, in contrast, are amazing in a far more troublesome way which deserves our attention.

The dangers of speedy information

A recent incident that stands out in my mind every time I come around to this topic is the confrontation between the Indigenous Peoples March and a group of high school students at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., earlier this year. If you didn’t hear about or don’t remember that incident, social media reports with brief videos that lacked critically important context spread like wildfire. The students involved were pilloried in the media and across the country and even received death threats, to the point that the school closed for a day. Later details revealed that the whole thing may have been a misunderstanding; at worst, some tired students in a complicated situation reacted to insults thrown at them in a less-than-commendable way.

This incident is so telling to me; it’s the archetype of all today’s social media commotions. The initial reports of an incident that thirty years ago would have merited at most a column in the local newspaper became viral by pure accident and were spread across the world within hours by people who had no knowledge of what happened. The resulting reports were largely wrong, with disastrous results for the people depicted in the videos. Once the dust began to settle, the whole thing backfired again on the people who shared the information, because many of them made comments about the incident in public forums, some of them quite offensive even without the later details. A number of people were fired for their hasty tweets, and many major news organizations were publicly embarrassed.

Meanwhile, what do we gain from the ability to see incidents like this blown out of proportion? I’d argue pretty much nothing. The few benefits of learning about minor news incidents immediately are part of a race to the bottom: maybe, if we read the news a little sooner than everyone else, we can convince other people we’re on top of things, or feel like we’re knowledgeable and connected ourselves, or get an edge in the stock market. Then again, maybe not even that: in his book The Black Swan, thinker and statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb claims that when he was a trader, he one day decided to stop ever reading the news – down from multiple hours a day – and his performance suffered not one bit. Regardless, if everyone was on a news cycle of once per day, or once per week, nobody would be doing any worse on these fronts, since they’re all relative to other people. Yet we’d all be more relaxed, have more complete and accurate information, and spend less time keeping up.

Fear of missing out, nicknamed FOMO, is absolutely a real thing. It’s one of the factors that keeps us scrolling through social media, obsessively checking our notifications, making sure we follow all the important trends. Here’s the good thing: there’s so much going on, so much information available to you, so many great movies and books and TV shows and articles to consume, that you’re definitely going to miss out on a lot of great stuff – but that’s just fine, because you can still have more great stuff than you know what to do with! That is, unless you spend your time running on the hamster wheel trying to keep up with all the stuff instead of taking time to reflect on what stuff really matters to you and then working your way through that stuff. Unfortunately, running on the hamster wheel is what every user of social media and the modern web is doing to one extent or another, because the platforms encourage that behavior.

Don’t think it’s hopeless, though. It will take collective action by both tech companies and everyday people to make our information platforms less addictive and change our attitudes, and that’s not easy or fast, but you can do a few simple things today to begin untangling yourself. I haven’t by any means solved the problem for myself, but I have been experimenting with some behavior changes, and I’m pleased to say they appear to help.

The goals of slowing down, as I see it, are as follows:

- Reduce the amount of time we spend consuming information that has neither immediate nor lasting value. This category is the information equivalent of junk food: it feels good to consume in the moment, and the best of it is acceptable in moderation as a form of entertainment, but if we consume too much our minds will regret it later.

- Take advantage of time to filter out that information without value. Why do people always say music from 50 years ago was so much better? Some of it’s a matter of taste, but another huge component is that people stop listening to the bad and mediocre songs and artists after a few years pass – all but the best are forgotten. If a popular piece of news or a meme is particularly good or influential, we’ll likely hear about it sooner or later. If it’s not, then great, we didn’t have to bother ourselves with it.

- Be less distracted and more relaxed and worry less about missing out on the latest and greatest. The benefits here ought to be obvious.

Here are some techniques for achieving these goals.

Slowing down your flow of information

Take social media off your phone

The space you inhabit has a lot of power over your behavior, and that applies just as much to virtual space as physical space. You’ve undoubtedly heard diet gurus say that if you don’t want to eat some kind of junk food, you shouldn’t bring it home, to which you probably say, Well, duh. But it works.

If the Facebook app isn’t installed on your phone, the barrier to checking your Facebook feed becomes high enough that you won’t bother. And unlike food, if you suddenly legitimately need the Facebook app, you can download and install it from the app store anytime and anywhere, and it’ll only take you three minutes. Not having social media apps installed on your phone doesn’t imply that you don’t use social media (although if that’s what you want, I don’t think that’s an unreasonable choice); it just means you do it on your computer at your desk instead of when you’re lying in bed or out engaging with the world.

Actually, take anything off your phone that poses a distraction, if you can stand not to have it there. Don’t need your work email on your phone very often? Don’t put it there, and you won’t get dragged into reading your work email unless you actively decide to. I don’t have my work email, any social media, or any mobile games on my phone, and at times I’ve even disconnected my personal email. And it’s glorious. It’s not a hardship or an exercise in self-denial; it means I pay more attention to what’s happening around me, spend more time interacting with real, live people, have more time to think, and fall down rabbit-holes of distraction far less often. And it doesn’t mean I can’t use social media or play stupid games if I get in the mood to do so, it just means I do those things in specific contexts, rather than at random times when I absentmindedly pull my phone out. If I want to use my phone during a lull, I can still prune my to-do list, read, or study flashcards – things which do just as good a job at killing time but actually burn down my backlog of stuff I want to do instead of adding more to it.

Retrieve information only at designated times

You can take the designated-place approach above a step further and add a designated time as well. Aside from unusual situations, I’ve moved to only reading social media on weekends. I now spend less time reading unimportant things, still see most of the important things (especially on sites like Reddit where you can actively choose to see the top-rated content from the last week), and am way more relaxed during the week. Most of us have forgotten what it’s like to move at our own pace without being flooded by news and external demands, and let me tell you, it’s nice. You can set your own pace, but if you do what your tools are encouraging you to do and what everyone around you is doing, you won’t succeed. It’s up to you to make it happen.

The world is most sorely in need of this approach for social media, but it works for any kind of information you receive from the outside world, like your email or the news. Decide how often you want to see each of these things (say, work email once an hour, personal email and news once a day), then establish routines around checking each of them and ignore them completely outside of those times. You don’t have to actually handle all the content at that time, either; when I read the news, I just scan the headlines and add any interesting articles to my reading list, then I get the details over the next few days when I’m in the mood to read. As we discussed in the first half of this article, that amount of delay has no practical effect on the value of the news, and may even prevent us from getting caught up in inaccurate hype and making snap judgments.

Use a “read it later” service

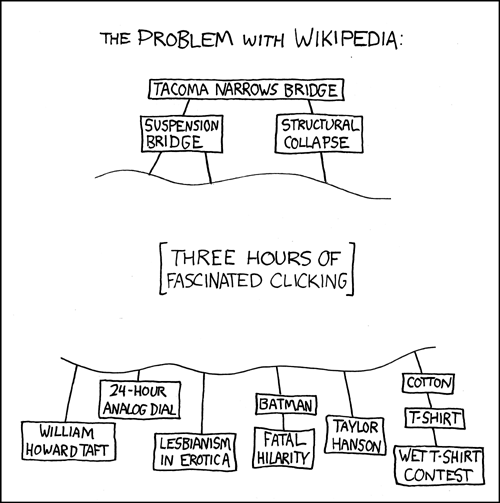

I enjoy reading and learning about random things, to the point that I’ve been known to waste most of a day on Wikipedia:

I’m sure most people don’t have this problem to the extent that Randall Munroe and I do, but I’m sure everyone has had the experience of clicking hyperlink after hyperlink, eventually to discover they’re now doing something entirely unrelated to their original task. The Internet’s various read-it-later services offer a potent weapon against this brand of distraction. I use Pocket, but other options are available. When you see an interesting article or page that’s not related to what you’re working on, you just right-click or long-press on the link and choose “Save to Pocket”, and the article drops into your reading list. You can stop thinking about it because you won’t forget about it, and when you’re bored you can pull up your list on any device and read. Pocket also strips most of the ads, funky formatting, trackers, and other goo from the articles, formatting them cleanly and consistently, reducing distractions while you’re reading as well.

Note: Pocket offers a vast array of other options for getting stuff onto your list, by using Share buttons, pasting URLs, connecting to third-party services, and so on. If you want to be able to import items by having your dog write down the titles and hold them up to your laptop’s webcam, you can probably find a way to make that happen. I might be exaggerating, but only a little bit.

Use notifications with care

Lifehacker brought an article with the inflammatory title “Notifications are Evil” to my attention a few years back. Notifications aren’t intrinsically evil – in fact, sometimes they’re great. But we treat them like a trivial, basic part of the background of modern life, like turning on the tap to get some water, when they ought to be treated like government forms or morphine or chainsaws: fantastically useful in the right circumstances, but somewhere between bothersome and lethal if misused, something to be exceedingly careful with. If there is evil to be found in notifications, it’s in the way many designers intentionally misuse notifications to subvert users’ attention for their product’s short-term gain – not at all unlike the way major drug companies have pushed opioid prescriptions to people who don’t need them.

Surely I’m exaggerating by comparing notifications to drugs that now directly kill more people yearly than car accidents, right? Probably – but I wouldn’t be quite so sure. Getting one notification too many won’t make your phone electrocute you or anything, but distraction, lost sleep, overuse and unhealthy use of social media and the Internet at large, and the attendant decline in real social interaction these things cause seem to be having a grave impact on mental health, and all of these problems are intertwined with misused notifications. This isn’t a trivial issue by any means.

So how do we use notifications correctly? Notifications, properly used, have three main roles to play:

- Interrupting you for unexpected pants-on-fire events: your company’s server is down and thousands of users have no service, your daughter got in a car accident, your sump pump stopped working and the basement is flooding. Effective notifications about these things mean you learn about them as early as possible and can react promptly to control the damage.

- Taking your mind off things: instead of constantly checking your calendar and watch and worrying you’ll miss an appointment, or trying to remember when your laundry will be finished, you can have notifications let you know when it’s time to pay attention. Or if you’re waiting for an important email, you can choose to get notified right away when that email comes in and stop nervously refreshing your inbox every five minutes.

- Letting you know when someone wants to talk to you immediately and synchronously. Usually this takes the form of a phone call or some kind of text message. Having notifications for this purpose allows us to have these useful and often meaningful conversations on demand instead of having to laboriously schedule them in advance.

Unfortunately, accepting the default settings in all your apps can result in dozens or even hundreds of notifications splattering across your devices each day, most of which don’t align with any of these roles. Every time you respond to a notification, you get jolted out of what you’re doing. If you were in the middle of something complicated, studies have shown you can lose as much as 25 minutes of productivity to each pointless interruption. And that’s not to mention how hard it is to enjoy a book or a movie or a conversation with your friends if you keep ducking out of it every five minutes.

I took the “digital health checkup” promulgated at the bottom of the Google homepage the other day. Unsurprisingly, the focus was on how Google products could help your relationship with technology, and one of the cool you-get-this-for-free features it called out was that, by default, YouTube doesn’t send you notifications between 10pm and 6am local time. Which, well, great, that’s better than the alternative of waking people up in the middle of the night to inform them of new YouTube videos they could be watching – but why should the YouTube app be sending notifications at all? New videos that you could go watch aren’t pants-on-fire events, they don’t help take your mind off things (unless maybe you’re uncommonly eager for some specific video to be released), and they don’t involve communicating with other people. Presumably Google offers notifications because they encourage people to open the YouTube app and ultimately see ads that earn Google money, but as a user, what can I possibly gain from up-to-the-minute notifications about new videos on YouTube? If I made my living publishing on YouTube, that might be a different matter – but then again, following your marketing data minute-to-minute isn’t much more useful than checking it a few times a day, and at any rate that’s a different problem that calls for a different tool.

App and device design doesn’t help here. More tools have begun to offer better notification options, but they’re still lacking. The next level of sophistication, which all of us deserve as people who desperately need to protect our attention, should involve targeted notifications based on flexible rules. We might term the current approach dragnet notifications: most tools send you a notification anytime it might be something you need to know about, resulting in heaps of informational bycatch. We need spear notifications – ones which skewer exactly the things we want to know about right away and grab them and only them, leaving the rest behind where we can sort through them later (or never).

I want to be able to set up and destroy spear notifications on the fly as my needs change: let me know right away when someone writes back in this particular email thread, let these six people text me while I’m on vacation and put everyone else on do-not-disturb, mute the group chat until twelve hours have passed or someone says my name or one of these trigger words. I also want communication tools to offer priority indicators and people to use them appropriately; if I could mark my texts as urgent or trivial depending on whether they contain time-sensitive questions or funny videos, people could set their notification options accordingly. (Outlook has a nice “priority” indicator you can set on outgoing messages, but too many people seem to treat this as a marker of how Important their email is, rather than how soon people need to deal with it. Certain Important People deem most of their outgoing emails to be Important by association, resulting in Outlook interrupting my work to inform me some silly announcement was just published that at best I need to read by next week. Some of them really are important, but they’re rarely urgent.)

A few tools already offer this kind of customization. In IT, server monitoring tools can do all of this and more, and it’s great. We need to bring that level of flexibility to consumer technology. And ideally someone should invent a federated standard for notification settings, so I can use a single tool that controls all of my notifications from one place and can easily swap between sets of options as appropriate. Modern smartphones have a notifications control panel, but today it’s able to expose only controls regarding how apps are allowed to notify you of things, not what they see as important enough to tell you about within those rules.

In the meantime, turn off as many notifications as you can stand, even if the lack of spear-notification options means you’re a bit slower on the uptake. (If you have to, tell people to pick up the phone and call you instead of using their usual channels if it’s urgent. You might even get them interested.) If you take your social media off your phone entirely, you’ll already be in much better shape than most. Don’t let any app that doesn’t use notifications for one of the three important roles send you notifications at all, and treat notifications as a privilege that apps earn; if they abuse it, axe the notifications or get rid of the app. Use the “do not disturb” functionality built into modern phones if people are bothering you and you want a break; you can choose specific people who get to ignore that barrier if you like. And turn off email notifications, full stop; they really are bad, because most people get uncountable numbers of emails every day, and people rarely use email for things that deserve your immediate attention, so the vast majority of email notifications are false positives.

Tip: Many email programs let you disable dragnet notifications but set up spear notifications for certain types of emails, usually using Filters or Rules of some kind, and that can be genuinely useful: for instance, at work I get notifications when someone’s request in our request system is waiting on my approval, so I can get my coworkers unblocked right away.