The Magic of Index Cards

I find that nowadays the humble three-by-five index card is extremely underappreciated. True, some of the former roles of index cards are much better served by computer systems (e.g., library catalog systems). But the fundamental nature of information hasn’t changed, and index cards offer a flexible way of relating to information that’s tricky to get any other way, even on a supposedly infinitely flexible general-purpose computer.

Index cards were, according to the information science mythology, invented in the late 1700s by biologist and taxonomist Carl Linnaeus (at the least, he seems to have been one of the first to use them). Linnaeus was struggling with what the paper I’ve linked calls “the first bio-information crisis”: his classification projects not only dealt with large amounts of information, the state of the art was changing rapidly for the 1700s. Correspondents were sending him new specimens and ideas regularly, and the new information could result in substantial changes to existing classifications, resulting in a workflow that standard notebooks did a poor job of accommodating. Index cards provided part of the solution – since they could be easily reordered without tearing apart a binding, inserting or adjusting items became far less work. (Linnaeus’s projects resulted in a number of other interesting organizational innovations; check out the link for some more.)

Computerized editing nowadays solves the insertion problem, and to some extent the reordering problem: you can add a new section or document anytime, insert new text in the middle of hundreds of pages just by clicking there, or do a quick copy and paste to move things around. If the usual tools like Word documents or text files or note-taking apps aren’t good enough, specialized outlining tools can make it even easier. But sometimes paper is easier to work with. And even more importantly, index cards match our thought processes much better than all but the most complicated of today’s apps, which tend to help us present information in a linear fashion rather than an unordered or flexibly ordered one.

Let me expand on that last part. Complicated projects often require us to keep track of many loosely related pieces of information. For instance, I’m working on upgrading a large piece of enterprise software at work right now, which requires changing some custom work processes that we’ve developed around it. I need to keep track of each of the processes that are changing and what the changes are, the icons and abbreviations I’ve had to use to make those notes readable and concise, the tasks I’ve determined I need to complete (tasks which fall into several subcategories, some of which are being done by someone else), general notes on how the system works, the steps to carry out various tests I have to run repeatedly as I work out more of the process, and a list of things not to forget when we make the move for real. Or consider writing a book: besides the actual manuscript, you need to keep track of your structure, a general outline of what you’re working on next, things you know you need to go back and revise, great ideas you had in the shower, your scenes and characters if it’s fiction, your citations and sources and contacts if it’s nonfiction, and so on and so forth.

The problem with these kinds of projects is twofold. First of all, the information you need often changes and reorders rapidly, just like in Linnaeus’s project. But more importantly in the digital age, we often need to see the information gathered by these projects in different and rapidly changing ways. We collect far too much information to see or work with at once, but from minute to minute we need different pieces of it. One day I might be working with three sources for my book and noting where I’m using information from them; the next day I’m sorting through all my random ideas and trying to figure out how to integrate them into my outline; and the next I need to look at Part 1 of my outline and its associated sources. What I want is to see only the specific information I need each day, so I don’t get overloaded with irrelevant stuff.

Most note-taking systems struggle mightily with this kind of requirement. You might choose to keep the information all mixed up in one document, or perhaps divide it up into different documents by the type of information (list of sources in one place, manuscript in another, todo list in another). In the first case, you have to constantly scroll around in the document. In the second case, you have to have six windows open at once, and even in 2019 almost nobody has enough screen space to comfortably look at everything. Even if you can fit all the documents on screen, you may only need a couple of pieces of information, but they could be vast distances apart from each other in the document, meaning you still have to scroll around all the time (or laboriously reorder the document and hope you don’t confuse yourself later). And if you’re keeping the notes in paper notebooks, it’s even worse!

This kind of information-scattering, aside from being just plain annoying, is a terrible distraction that hampers getting actual work done. Cards, on the other hand, are almost infinitely flexible. You can select exactly the cards you need to see at any given time, and keep the rest hidden away until you need them. As you reorganize your project or need to see things in a different order, you simply move the cards into different stacks or sections in a cardfile. If you have to rewrite a card because it’s so full of corrections you can’t read it anymore, it only takes a minute because there’s only a small amount of information on it, plus you get to review and reprocess that information as you rewrite it. If you need to see more cards at once than you have space for, you just pick up your deck and go find a bigger table. How’s that for scalability?

Index cards have another curious property: patterns and ideas can emerge from a stack of index cards just by studying and rearranging the cards. The effect is like that of shuffling your Scrabble tiles and suddenly seeing a brilliant move that just wasn’t there a moment ago. In college, I arrived at multiple essay topics by writing ideas and interesting bits of research on cards and then trying to group them into meaningful collections (which would often ultimately turn into sections or paragraphs). Dmitri Mendeleev is said to have hit upon the modern arrangement of the periodic table this way (like the story of Linnaeus “inventing” index cards, the exact truth value of this story is not entirely clear). And novelist Vladimir Nabokov wrote many of his books entirely on index cards, for many of the same reasons.

Of course, nothing is perfect; the downside here is that if your project gets to thousands of cards which don’t have an order or fall into neat categories and you have that one card that you need somewhere in a big pile, finding it may be a serious challenge. But most projects don’t have this amount of information to deal with. If yours does, you’re going to have challenges with any method of organizing it, and you’ll have to experiment and devise techniques that work for that individual project.

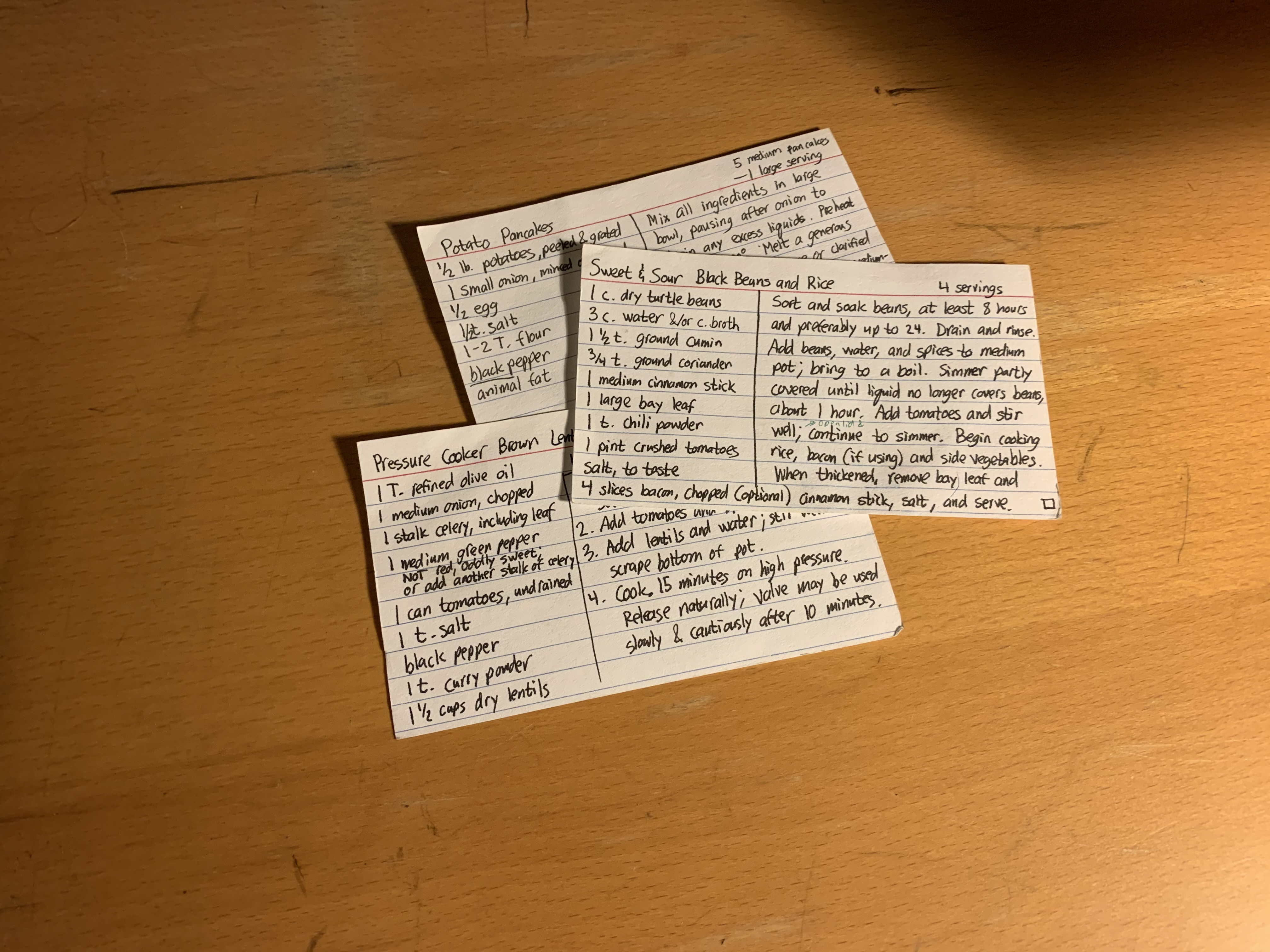

If you need some inspiration or you’re just curious, here are a few things I use cards for.

Tip: If you want something flexible and nonlinear like index cards, but you really need computer features like full-text search, tagging, and so on, check out TiddlyWiki, which describes itself as “a non-linear personal web notebook.” I’ve used it for projects before, and it brings a refreshingly new take to computerized note-taking and project management. Unfortunately running only in a browser involves certain irritating limitations, particularly with regards to saving changes, and you’re still limited by the size of your screen, but TiddlyWiki is a huge step up from a simple text file or Word document for organizing the kind of information discussed in this article.