Supplement on Emergency Contraception Effectiveness

In my post on contraception, I mentioned emergency contraception only in passing, as something that was out of scope, but it’s come to my attention that there are also important and underconsidered differences in effectiveness here, and that most people are woefully underinformed or even misinformed about EC in general, so here’s something to bring you up to speed if you need it.

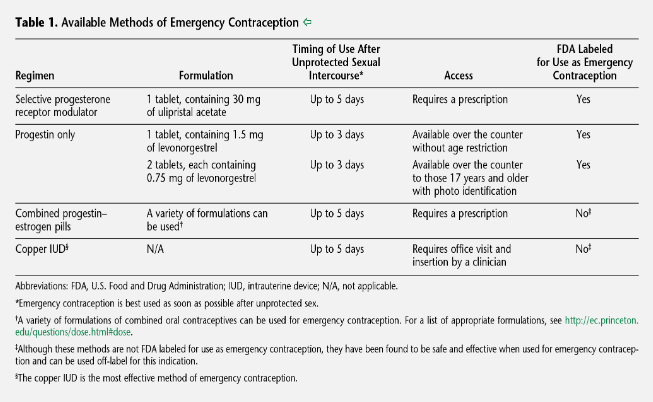

When I started looking at this, my mind was again blown by how little attention many sources give to effectiveness. For instance, symptomatic of the problem is this nice summary table at the top of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ practice bulletin on emergency contraception (if you want to read more about this topic, definitely check that out; it has great citations too). It gathers together many useful facts about each option, except, ya know, how well it actually works:

Even Planned Parenthood’s recommendations, which I otherwise liked and have linked a bit lower down, only rank the methods by effectiveness and don’t give any numbers, which is better than nothing but makes it hard to decide on the cost-benefit tradeoff of trying to get a more effective but more difficult option. This seems especially odd given that accessibility and effectiveness are pretty much the only considerations for emergency contraception; unlike standard contraceptives, since you (hopefully) only use EC a handful of times in your life, there’s little reason to worry about, e.g., the effort to use an EC method or what annoying side effects you’ll get from it.

Anyhow, enough ranting: let’s try to fix this gap. I’ve gathered together a few numbers and some information about how each option works that will help you reason about when one option might be more effective or useful than another.

Extremely important disclaimer again, maybe more important this time because the choices look a little more clear-cut here and this might look more like a recommendation: this is not medical advice, and I’m neither a medical professional nor a contraceptives researcher, I’m some dude on the internet who spent a few hours looking at reviews and papers to get an idea of what the world knows on this topic. My main goal is to offer a clear understanding of the space here so you’ll know what options you might want to look for should you ever need them. If you pick something to try based on this post, please double-check it with the current recommendations of an organization like Planned Parenthood or the WHO; something might have changed between my writing this and your reading it, or I might just have screwed up. And definitely read the package instructions before taking any drugs you haven’t used before; because this is not medical advice, I am not including details on how one uses them or what actions might be required afterwards.

If you’re reading this because you need emergency contraception right now, I highly recommend also checking out Planned Parenthood’s resource, “What kind of emergency contraception is best for me?”

What are emergency contraceptives for?

In case you’re not up on this, because a surprising number of people haven’t even heard of them: a woman (or anyone who can become pregnant) can use emergency contraceptives for a short period of time after having unprotected sex or sex where some contraceptive observedly failed (e.g., a condom broke, someone realized they missed doses of their birth-control pills). This is usually less effective than ordinary contraceptives used properly, but it can still greatly improve the chances of avoiding pregnancy. Options include medical devices (IUDs) and pills (sometimes colloquially called “morning-after pills”). Side effects are often noticeable but rarely troublesome.

Emergency contraceptives are not abortions – they are designed to prevent you from becoming pregnant, not to terminate an existing pregnancy. (However, it’s possible that one of the EC medications may be embryotoxic and/or cause miscarriages if you already are pregnant. See the Ella section for more.)

Takeaways

- Being able to take advantage of emergency contraception requires knowing that it’s a thing and roughly how it works – and a lot of people don’t – so figure that out now! If you are at risk of getting someone else pregnant, you should also know all of this even though you can’t actually use EC yourself, because public education on this is so bad that there’s a good chance your partner won’t know it.

- EC is more likely to work the sooner you use it. Depending on the method, you’ll get some benefit as long as 3–5 days after sex, but effectiveness declines over time at varying rates depending on the method. When you see percentage success rates here, these are averages: you can get a better figure if you act quickly and will get a worse figure if you act slowly.

- About 99.9% of people who have an IUD inserted avoid pregnancy. If this option makes sense, it’s a great one.

- About 98.7% of people who take Ella avoid pregnancy. If you’re not getting an IUD but you can get your hands on Ella, it’s very likely the best option. Unfortunately, it requires a prescription in the US.

- About 97.8% of people who take Plan B avoid pregnancy, and anyone can get it over-the-counter at any US pharmacy. Plan B needs to be taken more promptly than other options to be effective. Despite being less effective than Ella or an IUD, it’s still very much worth using if those options are impractical. Indeed, because it’s so easy, anyone who might plausibly need it should consider buying some ahead of time just in case.

- If you’re unable to access any of these options, you might be able to use a bunch of standard birth-control pills as an emergency contraceptive, but you’ll need to get advice from a doctor, pharmacist, or web reference for the specific type of pills you have. This is less effective and has worse side effects, so there’s no reason to choose this option unless all the others are unavailable.

Statistics note: Emergency contraception figures are sometimes given conditionally, as the proportion of pregnancies that would otherwise have happened and were averted by the contraception; this results in statements like “this EC method was 80% effective.” The numbers I’m giving are instead the (I think more legible) chance that, if you use this EC method to account for some particular occasion of unprotected sex, you end up getting pregnant anyway. In the 80% example above, this is conceptually the 20% chance of the EC not doing anything multiplied by the baseline chance that you get pregnant from unprotected sex (methods of actually calculating it may vary).

IUDs

By far the most effective option for emergency contraception is prompt insertion of an IUD; this gives only about a 0.1% chance of ending up pregnant afterwards. This should be done within 5 days of having sex to be effective; effectiveness doesn’t decrease much over that period. Depending on where someone is at in their menstrual cycle, it’s sometimes worth trying even later.

Few people are aware this is an option, which is a real shame because, astoundingly, this is about as effective at preventing pregnancy as having it properly installed before having sex, and it’s a full order of magnitude more effective than the next best option. Only the copper type is currently approved in the US for this use, but the hormonal type was found to be similarly effective in a widely discussed 2021 study, so if you can find someone willing to give it to you off-label this way and that type suits you better, that might be a good option too.

This option obviously has the convenient effect that (assuming you don’t decide to get it removed due to side effects) you get long-lasting, highly effective contraception for the next few years for free.

It’s worth mentioning that many researchers think the high effectiveness of these belatedly-inserted IUDs means they must at least sometimes function by preventing implantation of a fertilized egg. Most researchers and ethicists don’t believe this qualifies as an “abortion,” but some people believe it does, and if that possibility bothers you personally, you might prefer to avoid this option (and IUDs in general). The other options discussed below have been found not to involve this method of action.

Pills

If you don’t want an IUD, can’t get an appointment in time, or think it’s too much trouble for a situation that didn’t expose you to that much risk, three different pill-based options are available.

All of these options operate primarily (maybe entirely) by preventing or delaying ovulation. That means time is of the essence – if someone has already ovulated by the time they take the pill, it’s no use. For that reason, it’s plausible that a “less effective” option below could be more effective if you can take it sooner; see the Ella section for further discussion.

Note: Strong evidence suggests that Plan B does not prevent implantation of a fertilized egg – even though the packaging in the US says it “may.” (As far as I can tell, nobody thinks Ella does either, but this has not been studied as extensively.) As an odd historical footnote, this mislabeling, performed for political reasons, played a key part in a scientifically indefensible decision in the infamous Burwell v. Hobby Lobby US Supreme Court case. Read the full story of how this came to be in this oddly fascinating ethics paper.

According to some research, all of the pill options may be less effective in people who are overweight or obese, but results have been inconsistent. (I couldn’t figure out whether people think this is a matter of having an insufficient dose, or something else.) But if you are on the heavier side, it’s plausible that an IUD might have a larger comparative benefit in effectiveness over any pill, and Ella might in turn be comparatively better than Plan B. Planned Parenthood says that Plan B is less effective if you weigh more than 165 pounds, and Ella is less effective if you weigh more than 195 pounds; making this into a binary threshold of “works fine” or “less effective” seems kind of silly to me, but I guess it’s all the data is enough to support. (Just to show this isn’t actually all that clear, in Europe, regulators removed the 165-pound information from the package because they deemed the data insufficient to support it.)

All this said, most people think it’s unlikely that any option becomes totally ineffective at some threshold weight, and we definitely haven’t established one through research, so it’s always worth using any option you have over nothing.

Most of the medical organizations I could find say that there are no contraindications for using any of these pills (except possibly already being pregnant unknowingly – see the Ella section). The health benefits of preventing an unwanted pregnancy are massively larger than the potential side effects. This is true even for people who generally shouldn’t be using hormonal birth control. But as always, if you have any worries and have the option to, it’s a great idea to ask your doctor first!

Different pills should not be combined. Taking multiple doses isn’t any more effective than taking one and worsens the side effect profile, while taking Ella with something else can actually result in lower effectiveness than either alone, as their mechanisms of action cancel each other out (Ella prevents ovulation by blocking uptake of progesterone, while the hormonal methods disrupt it by creating a flood of synthetic progestogens).

Ella

The most effective of the pill options, by the numbers, is Ella (active ingredient ulipristal acetate). Ulipristal blocks uptake of progesterone, preventing ovulation (which is normally triggered by a sudden surge of progesterone around the 14th day of the menstrual cycle). The sources I found said that between 1.2 and 1.4% of people who take Ella end up getting pregnant anyway. It stops being effective when taken more than 5 days after sex.

Pedantic note: The manufacturer spells the name of the drug ella (all lowercase). I tried doing this and it made the whole post harder to read, so I am capitalizing it anyway.

Compared to Plan B (discussed below), Ella remains effective for longer in total; its mechanism of action can block ovulation later in the process than Plan B’s can. And it’s unclear exactly what the shape of the curve in effectiveness over time is, but the decline is definitely shallower than Plan B’s. Some sources and studies claim that Ella’s effectiveness does not decrease over time at all across the five-day window, but I’m pretty skeptical because this seems biologically implausible with the proposed mechanism of action – if it works by preventing ovulation, surely taking it later makes it more likely that someone has already ovulated and thus reduces the chance it works. Maybe there’s something I’m missing here, or there’s an important secondary mechanism. Or maybe the studies were insufficiently powered since Ella is quite effective at baseline? In any event, it seems that timing is somewhat less important for Ella than for Plan B.

The main problem with Ella is that you need a prescription to get a dose in the US and most other countries, which, if you ask me, is pretty stupid for something that is safe, embarrassing to ask for, and becomes ineffective if you can’t take it soon enough. However, it is available over-the-counter in most of Europe. If you have easy access to Ella, it’s likely a better choice than the hormonal options below.

Important emerging research, but highly speculative (updated February 2025): A growing medical consensus suggests that taking ulipristal acetate (the active ingredient in Ella) should be avoided if you are already pregnant due to potential harm to an embryo; this is the only good argument I can come up with for requiring a prescription. There is evidence of embryotoxicity (potentially causing birth defects), although it’s based almost entirely on animal studies, which are notoriously unreliable about this kind of thing. There is also preliminary evidence that it is an effective abortifacient when combined with misoprostol. Misoprostol usually succeeds on its own, so that a second drug increases its effectiveness is not enormously strong evidence that ulipristal acetate would cause an abortion alone. Further, the medical abortion protocol tested in the study used a higher dose than a normal course of Ella. But the difference in dose was only a factor of two (60 mg compared to 30 mg), which is a pretty small margin, so all in all it doesn’t seem out of the realm of plausibility to me that taking 30 mg could cause an abortion, or at least serious harm to an embryo, in some cases. To be clear, there’s no direct evidence of that as of this writing, but there’s also no evidence to the contrary, and the study did find that ulipristal has abortifacient effects at far lower doses than previously believed possible; as far as I’m aware nobody has yet tried to put a lower bound on how low a dose could work.

(Having read about the abortifacient effect, I naturally wondered if the possible secondary effect making Ella more effective when taken later might just be causing an immediate abortion. This is first-principles reasoning and I’m not an expert, but given that about 8–10 days usually elapse between fertilization and implantation, that seems unlikely to me: the half-life of ulipristal acetate is only 32 hours, and a full 30 mg of it causing an abortion is already speculative. Even if you had already ovulated the day before the unprotected sex – usually any earlier and the sperm and egg will miss each other – and waited a full 5 days afterwards to take the EC, you’d expect most of it to have worn off by the time there was an attempt at implantation. Maybe it could discourage implantation like some people are suspicious IUDs might, but even that seems like a stretch in the vast majority of cases. I am not aware of any mechanism that would allow progesterone modulation to harm a fertilized and unimplanted embryo.)

All this is to say, if you know you’re pregnant, you definitely shouldn’t take Ella – or, for that matter, any other emergency contraceptive, because it won’t work anyway. If you think you might be pregnant already, it would probably be smart to take a pregnancy test first (assuming it’s been long enough since the sex that could have gotten you pregnant that you could expect the test to register positive if you were), or use Plan B instead, which is considered totally safe during pregnancy (albeit useless).

(Not-medical-advice warning. I can’t find any source that talks about this seemingly obvious question, so I’m doing my best. Please evaluate this argument rather than taking it on faith.) Initially I had concluded that given the choice between taking Plan B now or Ella later, you should take Plan B now, since it’s more important to get the drugs working right away. But after revisiting this and writing the paragraphs above, I’m not so sure anymore, given that Ella sees a small to nonexistent dropoff in effectiveness over the short term. It definitely seems better to take Plan B right away than risk getting nothing, even if the risk is in your own motivation. But if you’re confident you can get Ella after a brief delay and you’re willing to jump through the hoops, that might be more effective than taking Plan B immediately. (Unfortunately, you cannot take Plan B right away and then try to get Ella later; as noted earlier, taking both reduces the effectiveness below that of either option alone.)

It might plausibly be worth trying harder to get Ella if you know where you’re at in your cycle and you’re very close to ovulating, so that it seems likely Plan B might not work at all anymore. On the other hand, if you’re just early enough that Plan B still has a chance to work, you might actually worsen your chances if it takes you a little while to get Ella. So I’m not sure this actually suggests anything except that it would be great if it were easier to get Ella right away!

If you can get pregnant yourself, you might consider asking your doctor if they’ll write you a prescription next time you see them, so you can grab some in case you need it later. If you can’t get pregnant and were hoping to get some for someone else, though, you’re out of luck.

Plan B

If you can’t get hold of Ella, Plan B (a large dose of levonorgestrel, used in standard hormonal birth control) is also reasonably effective, with about 2.2% of people who take it still getting pregnant. Plan B has a smaller window of effectiveness because it disrupts an earlier stage in the ovulation process; it becomes quite ineffective if taken more than three days after sex, and it has a much steeper dropoff in effectiveness over that time. If you’re going to use Plan B, it’s important to take it as quickly as possible.

Speculation: It’s unclear to me what portion of the reduced effectiveness of Plan B compared to Ella is due to its time-sensitivity. Its mechanism of action does mean that it can’t be as effective since it won’t work if ovulation has already reached a stage that Ella would still inhibit at the moment you take the pill, so it definitely isn’t just the timing. But my educated guess is that if you’re able to take either Plan B or Ella very shortly after sex, the effectiveness is somewhat more similar than the numbers would have you believe.

Fortunately, it’s much easier to get Plan B promptly than other EC methods: Plan B is available over-the-counter with no consultation or limitations throughout the US. Anyone of any gender and age can walk into the pharmacy and buy some, or order a box on Amazon. Some places might keep it behind the counter, but you can just ask for it.

This combination of facts suggests that if you ever have sex that could cause you or someone else to get pregnant while using contraception that could noticeably fail in some way, or you even think you might do that sometime, it’s worth grabbing a dose of Plan B ahead of time. Plan B is mighty cheap compared to a baby – or even an abortion – and having some at home makes it feasible to take a dose (or offer one to your partner) if you’re mildly concerned that something might have gone wrong, when you might otherwise have taken your chances rather than deal with going to a medical appointment or running to a pharmacy. Plan B has a manufacturer-recommended shelf life of four years (most drugs actually last longer than they’re rated for, but I don’t think I’d take any chances on this one!).

Note: A reader pointed out that if you’re planning to store a drug for a long period of time, the storage conditions matter a lot more than they otherwise would. Many if not most people keep drugs in places that frequently change temperature and humidity, often to values outside of the recommended ranges on the packaging, like a bathroom. Find a more stable spot for your Plan B (or whatever you’re not going to be using soon).

In case you’re wondering, studies suggest that making Plan B more available doesn’t increase sexual risk-taking. Oddly, it also doesn’t seem to conclusively reduce abortions, perhaps because still not enough people know about it.

Normal birth-control pills

This protocol is rarely used nowadays, but if, for whatever reason, you are unable to get your hands on a dose of Plan B in a reasonable amount of time, it’s worth knowing that you also have the option of taking an extra-large dose of most brands of standard birth-control pills (typically 8–12 pills taken in two batches 12 hours apart). This works with both the progesterone-only kind and the combined kind. Standard pills used this way are fussy, less effective than any of the purpose-built products, and have a worse side-effect profile (especially if they’re the combined kind), so they should be used only as a last resort.

I could not find any good broad effectiveness numbers, perhaps because they vary between types of pills. Since everyone agrees this is the worst option and should be used only when no other option is available, the numbers might not change anyone’s mind anyway.

If you’re going to try this, you need to look up the correct dosing for the particular kind of pills you have on hand. (If you regularly use birth-control pills, it might be worth looking this up now for the type you have in case you ever need it.) This information is readily available on the web, or you can ask a doctor or pharmacist. This method is often called the “Yuzpe regimen”; you might have an easier time finding the data if you type that in.