Less-Quantifiable Benefits of Automation and Process Improvement

An engineer is someone who will spend three hours figuring out how to do a two-hour job in one hour.

Anonymous

It’s easy to read this old piece of wit as a joke at the engineer’s expense, and probably it was originally intended to be one. But contrary to popular belief, even in the most capitalist context, automating a task or making it easier and “more efficient” doesn’t have to be all about saving time or money, at least not directly at the point of doing that task. Sometimes it really does make sense to spend three hours figuring out how to do a two-hour job in one hour.

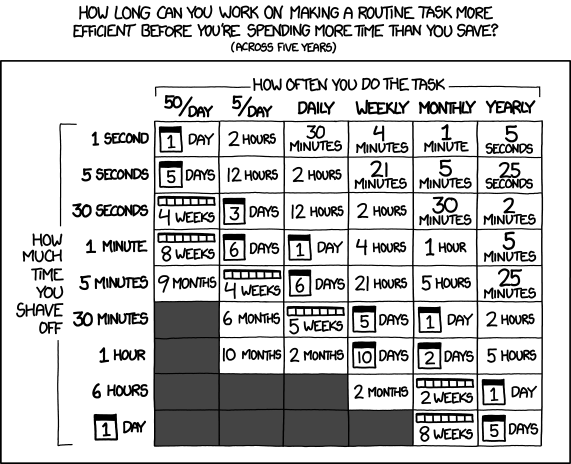

xkcd weighed in on this question in 2013, with a chart that could actually be useful when considering how much time it’s worth spending on a task:

Despite the rigorously mathematical and practical aesthetic of the comic itself, the mouseover text seems to sarcastically point to the ideas in this post, that looking only at the time misses the point:

Don’t forget the time you spend finding the chart to look up what you save. And the time spent reading this reminder about the time spent. And the time trying to figure out if either of those actually make sense.…Remember, every second counts toward your life total, including these right now.

Obviously, saying that it makes sense to take a loss on time and/or money now, and maybe even permanently, disobeying the xkcd chart, implies that there must be other benefits to automation and other kinds of process improvements besides the obvious efficiency gains. Let’s talk about some of those today.

Note: I’m passing over perhaps the very most obvious case precisely because it’s too obvious to require much discussion: when it’s worth losing lots of time now or in the general case to save a small amount of time at a specific critical point in the future. For instance, purchasing and mounting a fire extinguisher on the wall in a chemistry lab takes much longer than it would take to run out of the room and down the hall for the other fire extinguisher in the event that someone needed it, but sensible people are willing to spend an extra two hours when they set up a lab to save two minutes if someone’s experiment catches on fire, given that those two minutes could easily make the difference between a few scorch marks and rebuilding the entire lab!

Reducing mental effort

Some tasks require a disproportionate amount of effort compared to the amount of time they take. At my college, which was situated on a steep hill, you had to climb probably sixty stairs to get from the athletic building to the rest of campus. Students always joked that the hardest part of their workout was coming back up the stairs to campus. Of course, the stairs weren’t really that hard for reasonably fit college students who all walked up similar numbers of stairs multiple times a day due to the aforementioned campus geography, but the circumstances sure made it feel that way.

One task I find disproportionately irritating is looking up the day’s weather forecast or the current conditions. I have to either go to the computer or pull out my phone, open the appropriate app or website, wait for it to load, look through a bunch of details that I’m not interested in like tomorrow’s weather, and probably get distracted and look at something else. As a result, I wrote a little program where I type “weather today” or “weather now” at my command line and get exactly the information I care about, nothing extra and no ads:

$ weather now

***** ACTIVE ALERTS at this location. *****

Cur @20:07 &55060 DarkSky:

COND Overcast

TEMP 0.2

ATMP -19.5

DEWP -4.8 (79%)

BARS 1019.4

WIND 15.7/25.0 WNW

CLDC 96%

VISB 5.2

NSTM 74.0

Note: Yeah, the temperature and apparent temperature (ATMP) are degrees Fahrenheit. Not only am I in Minnesota in January, we’re expected to set 25-year temperature records this week.

Does this program save me any time at all? Not really! Maybe if I already have a command line open in front of me, I save two seconds over tabbing over to my browser and clicking the weather icon on the front page. Meanwhile, I spent at least five hours writing this program, so since it would take 30 repetitions to save one minute, I’ll have to do this 30×60×5 = 9000 times before I break even. By the time I want the weather forecast 9000 times, I will certainly have found another way to do it. But it certainly feels a lot better. In fact, it feels like I’ve saved myself time every time I use it, even though the analysis above proves I haven’t.

Reality is important, but sometimes perception matters just as much as or more than reality. Don’t focus too hard on reality just because you’re looking at efficiency.

Reducing mistakes

Computers, unlike people, do things exactly the same way every time. They don’t come to work sick or sleep-deprived, they don’t daydream, and they don’t check Facebook while they’re driving. Software doesn’t break or rust; once someone gets it right, it’s right. That’s not to say there can’t be bugs in software, or that difficult-to-troubleshoot problems caused by interactions between different systems never appear suddenly (because there are, many, and they do, frequently) but software overall is incredibly reliable compared to the number of tasks it performs.

People are especially bad at reacting to problems that occur rarely. Imagine I have a stack of a thousand index cards that I flip through, one per second. Each card has either the number 1 or the number 2 on it. When you see a card with a 2 on it, you push a button. Easy, right? Now suppose there’s only a single number-2 card in the entire deck. What do you think are the chances you’re actually going to spot the number-2 card and push the correct button? They’re probably decent at first, but the longer you go seeing only 1’s, the less likely you are to notice when the number-2 card comes up. After a few minutes, you’ll almost certainly start daydreaming, and you might well not notice the 2 in time to press the button, if you’re even still looking at the cards.

Now, deploying some software wrong, forgetting to go to an appointment, or overdrawing your bank account when the 2 shows up one in a thousand times might not be a life-threatening disaster, but you’d still presumably prefer not to do any of these things. It probably does take more time to let a computer take care of these things, like typing all your appointments into a phone or computer rather than trying to remember them or even just scribbling them on a scrap of paper. But most people nowadays find them worthwhile anyway, partly because we don’t have to rely on ourselves to remember as carefully: if we forget, the computer beeps and reminds us we have an appointment or our bank balance is getting low.

Mistakes often cost far more time, money, and frustration than automating or improving a process. Not only that, since mistakes are inherently unpredictable, while the cost of making improvements is at least somewhat subject to estimation, improvements can act as a form of insurance.

Tip: Preventing mistakes through process improvement isn’t limited to systems that can be automated. Simple checklists or regularly-followed documentation can help prevent many of the same kinds of mistakes, if somewhat less effectively.

Preparing for the future

Once you’ve reached a basic level of proficiency at it, doing a repetitive task (say, manually renaming a hundred files on your computer) gains you nothing except completion of the task. Doing the task in such a way as to improve the process results in both completing the task and improving your skills. For instance, let’s say instead of renaming 100 files by hand, I take five minutes to go on Google and research options for renaming 100 files. Let’s say in those five minutes I don’t learn anything about how to actually automate this task, but I do learn that instead of slowly double-clicking on each file in sequence to rename it, I can press F2 to rename the currently selected file, type the new name, then press Enter and the down arrow to select the next file. If that saves me two seconds every file, which seems reasonable unless I’m very quick with my mouse, I took 300 seconds to look up the information and saved 200 seconds on performing the actual task. Well, I’m down 100 seconds…but in this case, the next time I have to rename 100 files, I come out ahead. I can even share my new knowledge with anyone else in the office who needs to rename a bunch of files and save them 200 seconds as well.

Similarly, when I sit down to write a script to perform some task I’ve noticed myself doing repeatedly, I nearly every time end up going back to previous scripts I’ve written to look at how I solved those problems, and often copy and paste substantial chunks of solutions that would have taken many minutes to figure out again. The more you do, the more reference material you have (in your head as well as on paper!) and the faster it becomes to do it again. It’s next to impossible to estimate or predict what these benefits are going to be, but they’re definitely there and steadily accumulating.

Practical tip: The common counterargument is, “I’m so busy! How can I find the time to do that research?” Well, as the example hopefully showed, thanks to the wealth of information on the Internet, it might literally take only a couple of extra minutes. If you have a little bit of patience and squeeze it in, the gains will soon start to make themselves obvious.

For some thoughts on how to improve processes incrementally, have a look at the fabulous article Manual Work is a Bug. The author is a system administrator and focuses on that job, but many of the article’s ideas are equally applicable to any area of life, even ones that are incompatible with the article’s final stage of formality, a single piece of software created for the express purpose of completing that specific task from beginning to end.

On the negative side: losing invisible effects

Of course, automating things or even just making things a little easier can have negative effects too, from people losing their jobs to classic paradoxes and ironies. But besides that, no two solutions to one problem are ever exactly the same, and if we overlook the differences it’s easy enough to find a “more efficient” solution that actually has worse overall utility.

Sometimes the differences are so minor or the advantages of one solution over another are so large that choosing one of the solutions would be unforgivably silly. For instance, it would be absurd to claim that renaming a million image files to be numbered from 1 to 1,000,000 by manually selecting each one and clicking the “rename” button has any significant advantages over using a renaming tool to do it automatically. We can still think about the possible advantages – namely that a person might spot something that didn’t fit the pattern or needed special consideration – and try to work those into the superior process, say by manually spot-checking the completed images or creating a backup in case something doesn’t go right or following some kind of test plan for the automatic solution. But nobody who was capable of performing both methods would seriously consider actually using the manual method.

Other times, though, we leave something significant behind without noticing it. Recently, a number of studies have suggested that typing notes during a lecture is a remarkably bad study strategy: writing out notes by hand virtually always results in markedly better memory. The central problem seems to be that the act of having to choose what words to write down (because otherwise nobody using normal handwriting can keep up with the lecturer) oddly helps us remember the content. To quote from Scientific American:

Obviously it is advantageous to draft more complete notes that precisely capture the course content and allow for a verbatim review of the material at a later date. Only it isn’t.

There also seems to be some scattered evidence, if less clear, that the act of physically drawing lines has cognitive benefits.

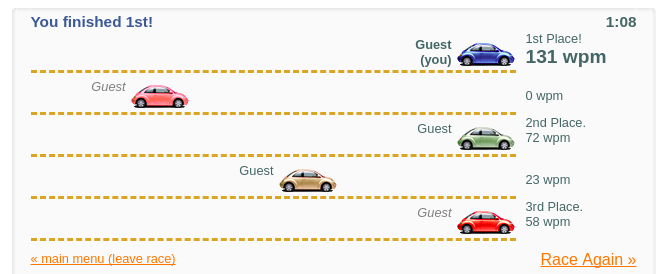

I can hand-write comfortably at only about 50 words per minute (and that’s using my proprietary blend of abbreviations and funky shorthand symbols). I can type at upwards of 120 wpm; just for fun:

There is barely any situation in which I could argue that handwriting anything longer than a sticky note could possibly be an increase in immediate efficiency. But I actually write a lot by hand in paper notebooks, particularly my daily journal, which is hundreds of thousands of words long. It’s slow…which is exactly the point. Typing is fast and mechanical, not reflective, and it doesn’t have the same effects on memory. Here’s where it’s worth not changing even though changing actually is more efficient.

Conclusion

It’s natural to want to sell the amount of time or money saved by a new-and-improved solution, whether to your customers, your boss, your friends, or just yourself. Next time you find yourself going this way – especially if the value isn’t looking so obvious but you care about the solution – zoom out a bit and look at the whole picture. What other benefits (or drawbacks) are you missing?